- Home

- Rob Brezsny

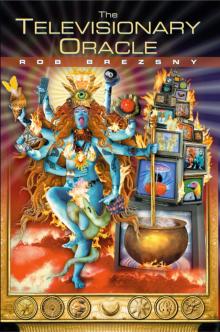

The Televisionary Oracle Page 7

The Televisionary Oracle Read online

Page 7

I want to direct your attention now, beauty and truth fans, to the archaeological evidence remaining from a death I created some years ago. It’s one of my favorite deaths, one of the bravest.

Look at the center of my forehead. Do you see the beauty mark I was born with—the icon-like bull skull with one horn slightly smaller than the other? Of course you don’t. Because it’s not there. Or is it? Better make sure. Deaths can be faked, after all. Zoom in and examine the area in question very closely. Maybe my treasure is simply buried beneath a slab of special-effects make-up. I’m rubbing. I’m scraping. Any pancake coming off? No. Because there isn’t any.

The grotesque yet beautiful glyph, the signature the Goddess imprinted on me in the womb, is gone. The birthmark that the ancient prophecies of our mystical order said would be the single most irrefutable sign of the female messiah. Disappeared. Erased. All that remains is what for all you know is a couple of worry lines.

My body has been re-engineered. I’m not the organism I was born to be. How? Why? Divine intervention? Miracle hands-on healing?

No. My gift is gone because I had it scoured away. At the tender age of sixteen-going-on-seventeen. Without parental consent. In a distant city, where I’d run away. With the help of a mere dermatologist who had never heard and will never hear of the Menstrual Temple of the Funky Grail.

But wait. Not so fast. My personal story makes no sense unless I embed it in a bigger, older story. And the victorious death I want to pull off for your entertainment pleasure won’t have the finality it deserves unless I prove to you the profundity of its ignominy.

Let me then show you how my sublimated suicide depends for its authority on evolutionary trends that are thousands of years old. They feature an organization whose money and wisdom are making it possible for me to be talking to you right now. This organization, the Menstrual Temple of the Funky Grail, is so old and vast—yet so precise and slippery—that only a fool would try to describe it. It’s a hundred organizations in one. A mystery school that’s more ancient than the sphinx. A think tank that’s so young most of its research is in the future. A media coven. A dream hospital. A gymnasium where mystical athletes hone their physical skills.

Picture a dating service for single mothers, or a secret society of occult astronomers that knew of the planets Uranus and Neptune and Pluto thousands of years before modern astronomers “discovered” them. Imagine a lobbyist for the rights of menstruators, or a ritual theater group that fed ideas to French playwright Antonin Artaud in his dreams. Visualize a gang of sacred janitors, or the world’s oldest manufacturer of sacred dolls.

Most of all, beauty and truth fans, picture a hidden sacred city of the imagination—temples, dream sanctuaries, gymnasiums, theaters, healing spas, love chambers—kept so secret that it’s invisible to all but a very few in every generation. Call this place a thousand names. Call it the College-Whose-Name-Keeps Changing-and-Whose-Location-Keeps-Expanding, or call it the Sanctuary-Where-the-Thirteen-Perfect-Secrets-from-Before-the-Beginning-of-Time-Are-Kept. Its official name as of today is “Menstrual Temple of the Funky Grail,” and it has headquarters on all seven continents. Five thousand years ago, it was housed solely on two continents as “Inanna Nannaru,” derived from Akkadian words, translated roughly as “Inanna’s Nuptial Couch in Heaven.” Six thousand years ago: “Tu-ia Gurus,” from the Sumerian, loosely meaning “Creation-Juice, Bringer of Good Tidings to the Womb.”

Two thousand years ago—so this story goes—our mystery school that is always both outside of time and yet entering time at every moment was called Pistis Sophia—in English “Faithful Wisdom.” Its most famous member—its only famous member—was Mary Magdalen, visionary consort of Jesus Christ. Not a penitent prostitute, as the Christian church later distorted her in an attempt to undermine the radical implications of their divine marriage. Not an obeisant groupie who mindlessly surrendered her will to the man-god.

On the contrary, beauty and truth fans. Magdalen was Christ’s partner, his equal. More than that, she was his joker, his wild card: his secret weapon. They worshiped the divine in each other. So say the ancient texts of our mystery school.

But you need not believe the secret texts to guess the truth. Even the manual of the Christian church itself, as scoured of the truth as it is, strongly hints at Magdalen’s majesty. While all the male disciples disappeared during the crucifixion, she was there with Christ. While the twelve male disciples were cowering in defeated chaos, she was the first to find the empty tomb. Jesus appeared to her first after his resurrection; she was the first to be called by him to the mission of apostle.

The Gnostic texts from Nag Hammadi, discovered in 1947, reveal even more of their relationship, which violated all the social norms of their time. She was a confidante, a lover, an Apostle above all the other Apostles. Jesus called her the “Woman Who Knew the All,” and said she would rule in the coming Kingdom of Light. Even an early Christian father, Origen, helped propagate these truths, calling her immortal, and maintaining that she had lived since the beginning of time.

The traditions of our ancient order say all this and more: that Mary Magdalen’s performance on history’s stage was an experiment—Pistis Sophia’s gamble that the phallocracy was ripe for mutation.

That the risk failed is testimony not to Magdalen’s inadequacies, but to the virulence of out-of-control masculinity. Magdalen, alas, was too far ahead of her time to succeed in being seen for who she really was. Her archetype was not permitted to imprint itself deeply enough on the collective unconscious. Sadly, the divine feminine barely managed to survive in the dreams of the race through the defanged, depotentized image of the Virgin Mary—Christ’s harmless mommy, not his savvy consort.

From her cave in Provence, twenty years after the death of Christ, Magdalen foresaw that the future Church would suppress her role in the joint revelation. She predicted the Council of Nicaea, which in the year 325 excised from the Bible all texts that told of her complete role. She even prophesied that the spiritual descendants of Peter, the Apostle who had hated and feared her most, would trump up the absurd story of her whoredom, conflating her with Mary of Bethany and three other unnamed women described as sinners and adulterers in various books of the freshly canonical New Testament.

In the last years of her life, Magdalen, knowing that her work with Christ would be foiled and distorted, prepared for a renewal of the experiment at a later time. The records of Pistis Sophia tell us that she wrote of the signs by which future members of our order would know she had reincarnated. These signs were as follows.

1. Her return would come in the last half-century of the second millennium, and she would be born in the astrological sign of the Bull.

2. She would be born “in the place called Holy Cross, in a land blessed by Persephone.”

3. She would endure “a living crucifixion that would save her life.”

4. She would “be conceived double but be born single.” In recording this prophecy, Magdalen added the following words, which are attributed to Jesus in the Gnostic Second Gospel of Mary Magdalen:

When you make the two one, and when you make

the inside like the outside and the outside

like the inside, and the above like the below

and the below like the above, and when you make

the male like the female and the female like the

male, then you will enter the Kingdom.

5. She would have a signature of the bucrania (or bull skull) in three places on her body: behind the left knee, in the right fold of the labia majora, and in the middle of the forehead.

In 1948, the Pomegranate Grail, which is what the Menstrual Temple of the Funky Grail was called at that time, began its preparations for the return of the avatar. Members all over the world were put on alert. Much attention was focused on all those places that were literally called “Holy Cross”—or in Spanish, “Santa Cruz.” Pomegranate Grail members congregated around Holy Cross College in Maryla

nd, as well as in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canary Islands, and Santa Cruz, California. Of these three, the Californian city aroused greatest excitement because according to one interpretation California was “Kali’s land.” Kali, in the canon of the Pomegranate Grail, was the Hindu equivalent of Persephone.

In anticipation of her search for the reincarnation of Mary Magdalen, Vimala Nostradamus, one of the thirteen chiefs of the Pomegranate Grail, settled north of Santa Cruz, California, in October of 1949, where she began to build the community that was to serve as the nest for the coming again of Mary Magdalen. Vimala had spent the previous ten years in Pondicherry, India, which at the time was the world headquarters for our order.

I faithfully report these facts to you, beauty and truth fans, because I can say without much exaggeration that my body is made of them. They were fed to me with my childhood meals, sung to me as I fell asleep, repeated to me as I was bathed, by the people who’ve loved me most and treated me best in life: Vimala and my six other mothers, Artemisia, Dagmar, Cecily, Sibyl, Burgundy, and Indigo. How could I doubt the veracity of these stories, when they come from the same nurturers who’ve helped make me so strong and healthy and confident?

And yet I have to say that it has always been easier for me to love those big, ancient tales than the implication they have for my personal life. The glory and the mission of Mary Magdalen are myths I have been able to appreciate best when I’ve tried to pretend that she wasn’t me.

But the people who’ve treated me best and loved me most say that Magdalen is me. I am, according to them, the fulfillment of the prophecy. Their avatar. The reincarnation of the divinity that last inhabited the earthly body of Mary Magdalen—come again to formulate and disseminate the new covenant of the ancient feminine mysteries, the dispensation for the next cycle of evolution.

And oh by the way, there won’t be any next cycle of evolution if I fail to do my job. The prophecies of Magdalen, supplemented by those of her most esteemed interpreters down through the ages, are unambiguous about this. Unless I successfully lead the charge to restore the long-lost balance of male and female, patriarchy will literally exterminate the human species. By what means is irrelevant—nuclear holocaust, germ warfare or genetic engineering gone astray, global warming or ozone-layer destruction or rain forest depletion. There is only one logical outcome to misogynist culture’s evolution, and that is to commit collective suicide.

According to the prophecies, it would almost be too late by the time Magdalen was born again. The patriarchy would be in the final stages of the self-annihilation it mistakes for aggrandizement.

Maybe you can begin to guess why I began to impose, at an early age, a buffer of skepticism between me and the role I was supposed to embrace. How many children are told that they have come to Earth to prevent the apocalypse?

At moments like these, I hallucinate the smell of a cedar wood bonfire. Visions of magenta silk flags flash across my inner eye, and tables heaped with gifts for me. These are psychic artifacts from midsummer’s eve six weeks after my sixth birthday—the day of my “crowning” as the avatar. For a long time my recollections of that day were a garbled mass of other people’s memories, which I had empathized with so strongly I’d made them my own. With the help of a meditation technique I call anamnesis, I have in recent years recovered what I believe to be my own pure experience.

I awoke crying that morning from a terrible nightmare, which of course I wasn’t allowed to forget, since Vimala was there, pouncing from her bed in the next room with her cat-smother love, asking me what I dreamed and scribbling it down in the golden notebook she kept to record every hint of an omen that ever trickled out of me.

I dreamed I was doing somersaults down a long runway, dressed in a flouncy red-and-white polka dot clown suit and big red flipper shoes. Thousands of people were in the audience, but they were totally silent even though I thought I was being wildly funny and entertaining. Then I picked up a violin and began playing the most beautiful but silly music, and the crowd started to boo, and some people walked out. Vimala jumped up on stage from below and stripped off my clown suit and flippers. Underneath I was wearing a long magenta silk dress. From somewhere Vimala produced a ridiculously big and heavy crown that seemed made of lead or iron. It was taller than my entire body, and when she put it on my head I reeled and weaved all over the runway, trying both to prevent it from tumbling off and to keep myself from falling. The audience cheered and whistled and clapped. I broke into huge sobs, which woke me up.

“Did your dream make you sad?” Vimala soothed me, as she kissed my birthmark.

I said nothing, but slumped and wiggled my front tooth, which was hanging loose by a thread of flesh. Although I’d been crying in the dream, I stopped soon after I awoke.

“There’s no need to feel sad,” Vimala said. “How can you feel sad for even a moment when you are such a very powerful queen of life with so many blessings to give?”

I wanted to cry but I couldn’t bring myself to. Instead, I yanked at my tooth.

And then suddenly it was free. Blood geysered down onto my red silk comforter and I started to shake. Vimala instantly removed the sash from her kimono and pressed it against my wound.

“Lie back down, wonderful one,” she comforted me. “Rest a while. Here, give me that tooth and we will wrap it up for the fairies to come and take tonight.”

She climbed under the covers with me and held my head in the crook of her arm. I fell back asleep.

When I awoke Vimala was gone. I decided I would lie in bed until she came to summon me. As I wandered back to the memory of my dream, I wanted to cry again and even felt the beginning of a sob erupting in my chest. But by the time it reached my throat, it was forced, a fake. I let it bellow out anyway, and the pathos of it almost ignited a real sob. But that too aborted itself.

As I looked around my giant, pie-piece-shaped bedroom, trying to penetrate the numbness I felt about the signs of luxury I beheld there, I allowed myself to experience, for the millionth time, my oldest, most familiar emotion: a blend of gratitude and guilt for all my blessings.

There in the corner where the curved outer wall of my tower met one wall of this, my “Moon Room,” Sibyl had built me an astoundingly authentic play castle, complete with drawbridge, crenellated battlements, and three pint-sized rooms. Inside were all the accessories a child queen could ever hope for, including a treasure chest of jewels, conical hats topped with banners of silk, and a magic mirror.

Beside the castle was my art station, with every kind of clay, paint, and crayons I would ever need to create my masterpieces, along with feathers, leaves, crystals, glue, a small hammer and other tools, pieces of wood and nails—everything. Beside that was Sibyl’s handmade, three-story oak dollhouse, filled with perfectly crafted miniature wood furniture. The entire room was a riot of toys, dolls, books, music, and countless other objects designed to nourish my imagination and overwhelm me with the knowledge that I was the most beloved child who had ever lived.

The emerald green walls—what could be seen of them through the swarm of toys and props—had been handpainted by Artemisia with scenes depicting the thirteen stations of Mary Magdalen (as opposed to the fourteen stations of Jesus). The figure of Magdalen was portrayed by the most successful female characters from fairy tales, including, of course, Rapunzel herself.

And this was just one of my huge rooms on just one floor of the four-story enchanted tower where I lived with Vimala. And in each of six other homes which formed just a part of our larger community—which seemed for all I could tell to be centered entirely around my happiness—there was a special room just for me where I could go to stay with my other six adoptive mothers. I had—and still have—seven mothers! And each has always doted on me as if I were her only child, even though Sibyl, Cecily, Artemisia, and Burgundy have natural-born children of their own.

My blessings were prodigal, supernal, monstrous. My meals were without exception masterpieces; th

e recipes came from cuisines as varied as my mothers’ ethnic backgrounds. I had a thousand different outfits to wear, a hundred different shoes. My mothers conducted intricate, mysterious rituals at least once every new moon and full moon—mostly, it seemed, for my benefit—and streams of interesting women who seemed equally in love with me were constantly visiting on these and other occasions. I was read to, played with, massaged, hugged, and taught by a tag-team of seven smart, psychologically healthy women who never grew bored or impatient with me, because the moment they might be on the verge of submitting to those feelings they handed me over to a fresh substitute.

Not one of my mothers, not even once, ever gave me the slightest suggestion that I should be overawed by my abundance. No one ever manipulated me into behaving the way they wanted by threatening to withhold their love. And yet neither did they spoil me. I was expected to work in the garden, and clean up my toys, and be responsible for my emotions.

The guilt I swam in was apparently my own invention, devised under my own inspiration. Without any direction, as if drawing telepathically on the frustrations of underprivileged people I had never met, I somehow managed to conjure a chronic reflex that combined the feelings of “How can I possibly deserve such wonderful treatment?” and “Thank you so much, beloved Goddess.”

Not infrequently, I daydreamed about what it would be like to experience real pain. Having my hands cut off was a good fantasy, fueled by the Grimms’ fairy tale about the girl with no hands. I tried, ineffectually, to imagine what it would be like to have my mother die, as Sibyl said hers had when she was a child. At times I felt something like envy for the sorrow and agonies of characters in books.

Maybe this wouldn’t have been a problem if my seven mothers had decided to tell me about the experiences in my early life that qualified as tragic. Those traumas—the loss of my twin brother, my heart surgery, and my biological parents giving me away to Vimala—had all happened before I could talk, at an age when memory was shaping its records out of materials that could not easily be retrieved later.

The Televisionary Oracle

The Televisionary Oracle